By Michael Lydon

By Michael Lydon

The Monterey International Pop Festival is over, all over. And what was it? Was it one festival, many festivals, a festival at all? Does anything sum it up, did it mean anything, are there any themes? Was it just a collection of rock groups of varying levels of proficiency doing their bit for a crowd of thousands who got their fill of whatever pleasure or sensation they sought? Was it the most significant meeting of an avant-garde since the Armory show or some Dadaist happening in the ’20s? Was it, as the stage banner said, “Love, flowers, and music,” or was it Jimi Hendrix playing his guitar like an enormous penis and then burning it, smashing it, and flicking its pieces like holy water into a baffled, berserk audience?

Was it a hundred screaming freak kids with war-painted faces howling and bashing turned-over oil drum trash cans like North African trance dancers, or was it the thousands of sweet hippies who wandered, sat, and slept on the grass with flutes and bongos, beads and bubbles, laughing and loving softly? Was its spirit Simon and Garfunkel, singing like little lost lambie-pie castrati, or was it Ravi Shankar, rocking over his sitar and beating a bare foot while opening up a musical world to 7,000 listeners who, at his request, did not smoke for his three-hour concert? Rolling Stone Brian Jones was part of it, wandering for three days silent inside his blond hair and gossamer pink cape; so was a girl writhing on a bummer at the entrance to the press section; while no one helped, cameramen exhausted themselves recording her agony. Was it a nightmare and something beautiful existing together or a nightmare and many beautiful things existing side by side?

One is left only with questions that a mind be-sodden with sound and sound and sound and sound cannot answer. Saturday night Jerry Garcia of The Grateful Dead commented, “There’s a lot of heavy stuff going on.” Whether he meant music or acid or emotion or everything, he was right. Something very heavy happened at Monterey last weekend.

Those very odd three days began in Friday’s cool gray air as the first of the crowd began to circle through the booths of the fairground. The only word for it then was groovy. A giant Buddha stood in one corner, banners decorated with astrology signs waved, and everything the hippie needs to make his life beautiful was on sale: paper dresses, pins, earrings, buttons, amulets, crosses, posters, balloons, sandals, macrobiotic food, and flowers. There was a soul food stand, the Monterey Kiwanis had fresh corn on the cob, the Congregation Beth El had pastrami sandwiches, and hippies with the munchies snapped their fingers to the popping of the popcorn stand. In the Festival offices Mama Michelle of The Mamas and the Papas was hard at work doing everything from typing to answering the phone. Papa John was keeping his cool in his gray fur hat which he never once took off in the frantic chaos.

Nothing but chaos could have been expected. The whole Festival had been nothing more than an idea two months before in the head of publicist Derek Taylor and in the rush of preparation had changed itself many times.

At first it was to be a commercial proposition; then Taylor, unable to raise the money needed to pay advances to the invited groups, had gone to Phillips and Dunhill producer Lou Adler for bankrolling. Why not make it a charity and get everyone to come for free, they suggested, and suddenly it became not a money-spinning operation but a happening generated by the groups themselves, which hopefully would make some composite statement of pop music in June 1967.

The Festival was incorporated with a board of governors that included Donovan, Mick Jagger, Andrew Oldham, Paul Simon, Phillips, Smokey Robinson, Roger McGuinn, Brian Wilson, and Paul McCartney. “The Festival hopes to create an atmosphere wherein persons in the popular music field from all parts of the world will congregate, perform, and exchange ideas concerning popular music with each other and with the public at large,” said a release. After paying the entertainers’ expenses, the profits from ticket sales (seats ranged from $3.50 to $6.50; admission to the grounds without a seat was $1) were to go to charities and to fund fellowships in the pop field. Despite rumors that part of the money would go to the Diggers in both Los Angeles and San Francisco to help them cope with the “hippie invasions,” so far no decision has been made on where the money will go.

This vagueness and the high prices engendered charges of commercialism—“Does anybody really know where these L.A. types are at?” asked one San Francisco rock musician. And when the list of performers was released there was more confusion. Where were the Negro stars, the people who began it all, asked some. Where were The Lovin’ Spoonful, the Stones, the Motown groups; does a pop festival mean anything without Dylan, the Stones, and The Beatles?

“Here they are trying to do something new,” said the Fillmore’s Bill Graham, “and they end up with group after group just like the jazz festivals. Will anybody have the chance to spread out if they feel like it?”

But as the Festival unfolded it was clear that if not perfect, the Festival was as good as it could have been. The Spoonful could not come because of possible charges that could be brought on a pot bust they had helped to engineer to avoid a possession charge against themselves; it was rumored, moreover, that John Sebastian wants to spend all his time writing and that they are breaking up as a group. Two of the Stones are facing pot charges of their own in England. Smokey Robinson and Berry Gordy were enthusiastic about the Festival at first, John Phillips said, “then they never answered the phone. Smokey was completely inactive as a director. I think it might be a Jim Crow thing. A lot of people put Lou Rawls down for appearing. ‘You’re going to a Whitey festival, man,’ was the line. There is tension between the white groups who are getting their own ideas and the Negroes who are just repeating theirs. The tension is lessening all the time, but it did crop up here, I am sure.”

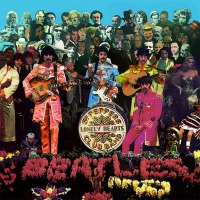

Phillips also reported that Chuck Berry was invited. “I told him on the phone, ‘Chuck, it’s for charity,’ and he said to me, ‘Chuck Berry has only one charity and that’s Chuck Berry. $2,000.’ We couldn’t make an exception.” Bob Dylan is still keeping his isolation after the accident which broke his neck last summer, and though rumors persisted up to the last minute Sunday night that The Beatles would show, or at least were in Monterey, they decided to keep their “no more appearances” vow. Dionne Warwick made a last minute bow out, and The Beach Boys, whose Carl Wilson faced a draft evasion charge, decided to lay low.

Yet as the sound poured out incessantly—the concerts with nary an intermission averaged five hours in length (can you imagine going to four uncut top volume Hamlets in three days, or sitting in the Indianapolis pits while they re-ran the race eight times over a weekend?)––gaps were not noticed. One dealt with what was at hand, and what was there was very, very good indeed. There were a few disasters who can be written off from the start. Laura Nyro, a melodramatic singer accompanied by two dancing girls who pranced absurdly; Hugh Masekela, whose trumpet is only slightly better than his voice—he did, however, do some nice backing for The Byrds on “So You Want to Be a Rock ‘n’ Roll Star,” and Johnny Rivers, dressed like an L.A. hippie, who had the gall to sing The Beatles’ “Help” not once but twice. Others, like The Association, with their slick high-schooly humor, didn’t fit in; still others, like Canned Heat, an L.A.-based blues band, had bad days. But the majority rose to new heights for the concert. There was the feeling that this was the place, that the vibrations were right, that one was performing for one’s peers and superiors, that anything and everything was one capable of was demanded. “I saw a community form and live together for three days,” said Brian Jones Sunday night. “It is so sad that it has to break up.”

That community was formed not only on the stage between the performers and the audience but backstage, at the artists’ retreat behind the arena called the Hunt Club, and in the motel rooms where parties went on till dawn. There was little off-stage jamming (no motels had the space, proper wall thickness, or power) except for a four-hour blast between the Dead, the Airplane, and Jimi Hendrix that carried the members to breakfast Monday morning after everyone else had gone home, yet everyone talked, listened, and grooved with everyone else. The variety of music was tremendous, blues to folk to rock to freak. There were big stars, old stars, comers, and groups who avoid the whole star bag. If one was good, in whatever bag, one was accepted. Music styles were not barriers; however disparate the criteria, there seemed to be some consensus on what was real music and what was not.

The Festival had a sort of rhythm to it that was undoubtedly coincidental—the organizers swore that there was no implicit ranking in the order of the acts—but which worked. Friday night was a mixed bag to get things moving, Saturday afternoon was blues, old and gutty and new and wild. Saturday night opened some of the new directions, then a return to peace with Shankar Sunday afternoon; and a final orgiastic freak-out Sunday night.

The Association began it all in the cool gray of Friday night with a professional style and entertaining manner, doing a fine job on their sweetly raucous hit single, “Windy.” Then The Paupers, a four-man group from Toronto, provided the first surprise. The almost unknown group, managed by Albert Grossman, Dylan’s grandmotherly and shrewd mentor, was able to get a screaming volume and a racy quality unmatched by some of the bigger groups. “I found them at the Whisky A Go-Go in New York,” Grossman said. “They were cutting The Jefferson Airplane to pieces so I signed them up.” Only together seven months they are sure to get better. “We are trying to create a total environment with sound alone,” said lead guitarist Chuck Beale. “Sound is enough. We don’t use lights or any gimmicks. When we record we never double-track or use any other instruments. What the four of us can do is the sound we make. That’s all.”

Lou Rawls, the blues singer whose “Dead End Street” is currently in the charts, came next and pulled the audience back to what he called “rock ‘n’ soul.” Backed by a big band, he looked as if he would have been more at home in a night club, but his fine funky voice and from-the-heart monologues about the nitty-gritty of Negro life were soulful indeed. To watch him was to be back at the Apollo where rock is flashy, stylish, and flamboyant, but still communicating with the kids high in the balcony. “The blues,” he said as he came off exhilarated, “is the way of the future. The fads come and go, but the blues remain. The blues is the music that makes a universal language.” Other music at the Festival seemed also to speak to all, but Rawls, a solid member of the professional black school of music, hit one major thread: the new music is still close to the blues, and most of the far-out sounds in the three days were but new blues ideas. He also had his finger on another key truth: “I’m trying to portray the facts as they stand. A few years ago rock was all facade, all doo-wah-diddy-diddy, all prettied up. I get the feeling that people now are trying their best to be where it’s at.”

After Johnny Rivers stayed on too long, Eric Burdon, one of the best white blues singers around, romped through a half dozen numbers with his new Animals, the high point coming with “Paint it Black,” the Jagger-Richards masterpiece which he, unbelievably, improved upon, particularly with the zany screechings of an electric violin. Brian Jones, sitting in the dirt of an aisle, applauded wildly.

Simon and Garfunkel finished off the night, and what can one say about them? “Homeward Bound” brought back memories of the time when a sweet folk-rock seemed to be the new direction, but though the song sounded nice enough, they seemed sadly left behind. “Benedictus” had them harmonizing like choirboys, and they did an encore, a funny new nonsense song, “I Wish I Was a Kellogg’s Cornflake.” When the last note floated out about 1:30 A.M., the first night was over and the peace was extraordinary. While the lucky (or unlucky?) few drove to their motels, the mass of the crowd drifted to the huge camping area near the arena and to the football field at Monterey Peninsula College nearby. There, with the sweet smell of pot drifting over sleeping bags, the music continued in singing and talking and in just being.

In the bright hot sun of Saturday afternoon the serious blues shouting began. Canned Heat led off with an uninspired set, and then came one of the most fantastic events of the whole shebang: the voice of Janis Joplin, singer of Big Brother and the Holding Company, a San Francisco group almost entirely unknown outside of the Bay Area. A former folk singer from Port Arthur, Texas, Janis was turned on a year ago by Otis Redding, and now she sings with equal energy and soul. In a gold-knit pants suit with no bra underneath, Janis leapt, bent double, and screwed up her plain face as she sang like a demonic angel. It was the blues big mama style, tough, raw, and gutsy, and with an aching that few black singers reach. The group behind her drove her and fed from her, building the total volume sound that has become a San Francisco trademark. The final number, “Ball and Chain,” which had Janis singing (singing?––talking, crying, moaning, howling) long solo sections, had the audience on their feet for the first time. “She is the best white blues singer I have ever heard,” commented S.F.Examiner jazz critic Phil Elwood.

Country Joe and the Fish, the acid-political group from Berkeley came next, and while they did not reach their accustomed heights, their funny satirical words and oddly dissonant music went over well. They did two of their political songs. “Please Don’t Drop That H-Bomb on Me, You Can Drop It on Yourself,” whose title is the complete lyric, and “Whoopie, We’re All Going to Die,” which contains the memorable line, “Be the first on your block to have your boy come home in a box.” These were among the very few explicit protest songs at the Festival; nowadays rock musicians are musicians first and protesters a slow second. “There are two parts to music,” said the lead guitarist and music writer for Country Joe, Barry Melton, “the music and the lyrics. Music we have with everybody, but some say the lyrics shouldn’t be political. Everybody agrees with us on the war, but we feel that in this society, you have to make your stance clear. Others don’t want to speak up in songs, be right up front. That’s why we put politics in.” Melton’s songs, particularly “Not-So-Sweet Martha Lorraine,” a nightmarish song about a mysterious lady who “hides on a shelf filled with volumes of literature based on herself” and who gets high with death, have been called “pure acid,” but Melton says all music is psychedelic. “One part of LSD is liberation, do what you want to do. I feel I do that, do what I want to do. When I hear a sound that is groovy I use it. I try to find music all over the place. Listening to anything can give you musical ideas. That’s freedom, and maybe that’s psychedelic.” He spoke for most of the groups. It would be hard to find any of the musicians who had not taken LSD or at least smoked pot, but by now it has become so accepted that it’s nothing to be remarked on by itself. Acid opened minds to new images, new sounds, and made them embrace a wild eclecticism, but rather than being “acid” as such, it has become music.

Al Kooper, an organist who has often played with Dylan, took half an hour with some funky blues organ and vocal, but the action began again with The Paul Butterfield Blues Band, a newly constituted version of the group that, more than any other group, led the revival of white interest in blues bands. Led by Butterfield’s fine voice and better harmonica, and with the strange melancholic whimsy of Elvin Bishop’s guitar, the backup band of bass guitar, trumpet, sax, and drums rocketed through some very impressive work. They also returned for the Saturday night show, with Bishop showing off his odd voice on a gloomy blues, “Have Mercy This Morning.” The Butterfield group, which began years ago, gigging with Muddy Waters in Chicago, knew, unlike Quicksilver Messenger Service and The Steve Miller Blues Band who followed, precisely what it was doing. Without being uptight, Butterfield was precise. They swung deftly on a broad emotional range, but the strongest memory is the haunting, looping sound of Butterfield’s harmonica as it broke a small solo of just a few notes into tiny bits and experimented with their regroupings.

The blues afternoon ended with a group that had no idea (apparently) what it was doing but did it with such a crazy yelping verve that it looked like in time it could do anything it wanted. Billed as The Electric Flag, it was the first time it had ever played together, and under that name it never will play again. Its leader, guitarist Mike Bloomfield, has been gradually building the band after leaving Butterfield’s group a few months ago. Its name in the future will be “Thee, Sound.” “As in ‘dedicated to thee, sound,’” says Bloomfield, “the whole world of sound, not just music.” Its set was an astounding masterpiece of chaos with rapport. Drummer Buddy Miles, a big Negro with a wild “’do” who looks like a tough soul brother from Detroit and who is actually a prep school-educated son of a well-to-do Omaha family, sings and plays with TNT energy, knocking over cymbals as he plays. Barry Goldberg controls the organ, and Nick “the Greek” Gravenites writes the songs and does a lot of the singing. The group was, for the groups present as well as the audience, a smash success. The Byrds’ David Crosby announced from the stage Saturday night, “Man, if you didn’t hear Mike Bloomfield’s group, man, you are out of it, so far out of it.”

The afternoon concert rode out with The Electric Flag on a wave of excitement that faltered in the evening concert. There was a curious feeling around late Saturday; everything was still very groovy, but the sweetness was going. The excitement of the music was getting too high. That stalled Saturday night but the level did not diminish. San Francisco’s Moby Grape led off the concert overshadowed by the rumor, fed by the ambiguous statements of the Festival management, that The Beatles would appear for the record arena audience of 8,500. The Grape had a driving excitement and some very nice playing with the four guitars, but no particular impression stands out. Masekela was terrible but Big Black, his conga player, was brilliant, holding up his reputation as the best conga player in the business. The Byrds were disappointing. Considered by many to be America’s Beatles, they were good, doing several new songs, but they lacked the excitement to get things moving. Butterfield was not as good as he had been in the afternoon and went on too long, and the evening hit bottom with Laura Nyro.

From there on things got better. Jefferson Airplane were fantastically good. Backed with the light show put on by Headlights, who do the lights at the Fillmore, they created a special magic. Before they came on the question hung: is the Airplane as good as its reputation? They thoroughly proved themselves. As they played, hundreds of artists, stagehands, and hangers-on swarmed on to the stage dancing. Grace Slick, in a long light blue robe, sang as if possessed, her harshly fine voice filling the night. In a new song, “Ballad of You and Me and Prunielle,” they surpassed themselves, playing largely in the dark, the light show looming above them, its multicolored blobs shaping and re-shaping, primeval molecules eating up tiny bubbles like food then splitting into shimmering atoms. The guitar sounds came from outer space and inner mind, and while everything was going—drums, guitar, and the feedback sounds of the amplifiers, Marty Balin shouted over and over the closing line, “Will the moon still hang in the sky, when I die, when I die, when I die.” They were showered with orchids as they left the stage.

In no time Booker T. and the MG’s were on rocking through some dynamic blues, and suddenly Otis Redding was there, singing the way Jimmy Brown charged in football. “Shake,” he shouted, “Shake, everybody, shake,” shaking himself like a madman in his electric green suit. What was it like? I wrote at the time, “ecstasy, madness, loss, total, screaming, fantastic.” It started to rain and Redding sang two songs that started slow, “to bring the pace down a bit,” he said, but in no time the energy was back up again.

“Try a Little Tenderness,” he closed with, and by the end it reached a new orgiastic pitch. A standing screaming crowd brought him back and back and back.

Day two was over and Sunday came gray and cold but the excitement was still there and growing. Could anyone believe what had happened, what might happen? Hours of noise had both deafened and opened thousands of minds. One had lived in sound for hours: the ears had come to dominate the senses. Ears rung as one slept; dreams were audible as well as visual.

Sunday afternoon was Shankar, and one felt a return to peace. And yet there was an excitement in his purity, as well as in his face and body, and that of the tabla player whose face matched Chaplin’s in its expressive range. For three hours they played music, and after the first strangeness, it was not Indian music, but music, a particular realization of what music could be. It was all brilliant, but in a long solo from the 16th century Shankar had the whole audience, including all the musicians at the Festival, rapt. Before he played, he spoke briefly. The work, he said, was a very spiritual one and he asked that no pictures be taken (the paparazzi lay down like lambs). He thanked everyone for not smoking, and said with feeling, “I love all of you, and how grateful I am for your love of me. What am I doing at a pop festival when my music is classical? I knew I’d be meeting you all at one place, you to whom music means so much. This is not pop but I am glad it is popular.” With that he began the long melancholic piece. To all appearances he had 7,000 people with him, and when he finished, he stood, bowed with his hands clasped to his forehead, and then, smiling, threw back to the crowd the flowers that had been showered on him.

Sunday night the Festival reached its only logical conclusion. The passion, anticipation, and adventure into sound had gone as far as any could have thought possible, and yet it had to go further. Flowers and a groovy kind of love may be elements in the hippie world, but they have little place in hippie rock. The hippie liberation is there, so is a personal kindness, openness, and pleasantness that make new rock musicians easy to talk to, but in their music there is a feeling of a stringent demand on the senses, an experimenting with the techniques of assault, a toying with the idea of beautiful ugliness, the creativeness of destruction, and the loss of self into whatever may come.

One of the major elements in this open-mindedness is feedback. Feedback is nothing new; anyone who has played an electric guitar has experienced it. Simply, feedback happens when a note from a vibrating string comes out of the amplifier louder than it went in and re-reverberates the string. The new vibration adds to the old, and thus the note comes out of the amp louder still. Theoretically the process could go on, the note getting louder and louder, until the amp blows out. In practice it can be controlled so that the continuing note is held as with a piano’s sustain pedal. That means that behind their strumming and picking, the musicians can build up a level of pure electronic noise, which they can vary by turning to face the amp or face away, moving toward it or moving away. Feedback can tremendously increase a group’s volume, produce yelps, squeals, screams, pitches that rise and rise, that squeak, blare, or yodel wildly. If nothing else, this Festival established feedback. One major test of each group was their ability in using feedback, and though it has many uses and effects, overall it creates a musical equivalent of madness. Every night featured feedback, but Sunday night was feedback night and a complete exploration of a new direction in pop music.

The night was foreshadowed by the first group, The Blues Project, the New York band that shares the new blues limelight with Paul Butterfield. Their first song featured electric flute in the hands of Andy Kulberg. It was part blues, part Scottish air, part weird phrases that became images of ambiguity. Big Brother and the Holding Company came back and were weaker than they had been, but one short number, “Hairy,” was a minute composed of short bursts of utter electronic blare, chopped up into John Cage-like silences. A group too new to have a name—The Group With No Name—was their billing—were terrible and may well not last long enough to get a name. Buffalo Springfield was totally professional, but largely undistinguished, except for a closing song, “Bluebird,” which alternated from the sweet sound to the total sound.

And then came The Who. Long popular in England where they achieved notoriety for their wild acts at London’s Marquee Club, they had never been seen in America. They were dressed in a wild magnificence, like dandies from the 17th, 19th, and 21st centuries. They opened with one of their English hits, “Substitute” (“I’m just a substitute for another guy, I look pretty tall but my heels are high”), with singer Roger Daltrey swirling around the stage in a gothic shawl decorated with pink flowers, and Keith Moon defining the berserk at the drums—he broke three drumsticks in the first song and overturned one of his snares. They had a good, very close sound, excellent lyrics, and the flashiest guitar presence of any group to appear.

Then John Entwistle, bass guitar, stepped to the mike and said, “This is where it all ends,” and they began “My Generation,” the song that made them famous. A violently arrogant demand for the supremacy of youth—“Things, they say, look awful cold, Hope I die before I get old”—the song has Daltrey stammering on “my g-g-generation” as if overcome by hatred or by drugs. After about four minutes of the song, Daltrey began to swing his handheld mike over his head; Townshend smashed his guitar strings against the mike stand before him, building up the feedback. Then he ran and played the guitar directly into his amp. The feedback went wild, and then he lit a smoke bomb before the amp so it looked like it had blown up, and smoke billowed on the stage. He lifted his guitar from his neck and smashed it on the stage, again, again, again, and it broke, one piece sailing into the crowd. Moon went psychopath at the drums, kicking them through with his feet, knocking them down, trampling on the mikes. The noise continued from the guitar as everything fell and crashed in the smoke. Then they stopped playing and walked off unconcerned, leaving only the hum of an amp turned on at full volume.

It was known to be a planned act, but, like the similar scene in the film Blow–Up (inspired by The Who), had a fantastic dramatic intensity. And no meaning. No meaning whatever. There was no passion, no anger, just destruction. And it was over as it began. Stagehands came out and set up for the next act.

That was The Grateful Dead and they were beautiful. They did at top volume what Shankar had done softly. They played pure music, some of the best music of the concert. I have never heard anything in music which could be said to be qualitatively better than the performance of the Dead Sunday night. The strangest of the San Francisco groups, the Dead live together in a big house on Ashbury Street, and living together seems to have made them totally together musically. Jerry Garcia, lead guitarist, and owner of the bushiest head at the Festival, was the best guitarist of the whole show. The Dead’s songs lasted twenty minutes and more, each a masterpiece of five-man improvisation. Beside Garcia there is Phil Lesh on bass, Bob Weir on rhythm guitar, Bill Sommers on drums, and Pigpen (who seldom talks) on organ. Each man’s part was isolated, yet the sound was solid as a rock. It is impossible to remember what it was like. I wrote down at the time: “accumulated sound like wild honey on a moving plate in gobs…three guitars together, music, music, pure, high and fancy…in it all a meditation by Jerry on a melancholy theme…the total in all parts…loud quiets as they go on and on and on…sounds get there then hold while new ones float up, Jerry to Pigpen, then to drums, then to Lesh, talking, playing, laughing, exulting.”

That sounds crazy now, but that’s how it seemed. The Dead built a driving, unshakable rhythm which acted not just as rhythm, but as a wall of noise on which the solos were etched. The solos were barley perceptible in the din, yet they were there like fine scrolls on granite. At moments Garcia and Weir played like one instrument, rocking toward each other. Garcia could do anything. One moment he hunched over, totally intent on his strings, then he would pull away and prance with his fat ungainly body, then play directly to some face he picked out in the crowd straining up to the stage. Phil Lesh called to the audience as they began, “Anybody who wants to dance, dance. You’re sitting on folding chairs, and folding chairs are for folding up and dancing on.” But the crowds were restrained by ushers, and those who danced on stage were stopped by nervous stagehands. It was one of the few times that the loose reins of the Festival were tightened. Was it necessary? Who knows? But without dancing, The Dead didn’t know how well they had done. Lesh was dripping with sweat and nervous as he came off, but each word of praise from onlookers opened him up. “Man, it was impossible to know how we were doing without seeing people moving. We feed on that, we need it, but, oh, man, we did our thing, we did our thing.”

They certainly did. The Dead Sunday night were the definition of virtuoso performance. Could anybody come on after the Dead? Could anyone or anything top them? Yes, one man: Jimi Hendrix, introduced by Brian Jones as “the most exciting guitar player I’ve ever heard.” Hendrix is a strange-looking fellow. Very thin, with a big head and a protuberant jaw, Hendrix has a tremendous bush of hair held in place carelessly by an Apache headband. He is both curiously beautiful and as wildly grotesque as the proverbial Wild Man of Borneo. He wore scarlet pants and a scarlet boa, a pink jacket over a yellow and black vest over a white ruffled shirt. He played his guitar left-handed, if in Hendrix’s hands it was still a guitar. It was, in symbolic fact, a weapon which he brandished, his own penis which he paraded before the crowd and masturbated; it was a woman whom he made love to by straddling and by eating it while playing the strings with his teeth, and in the end it was a torch he destroyed. In a way, the heavily erotic feeling of his act was absurd. A guitarist of long experience with Little Richard, Ike and Tina Turner, and the like, he had learned most of his tricks from the masters in an endless series of club gigs on the southern chitlin’ circuit.

But dressed as he was and playing with a savage wildness—again, how to describe it? I wrote at the time: “total scream…I suppose there are people who enjoy bum trips…end of everything…decay…nothing louder exists, 2,000 instruments (in fact there were three: guitar, bass, and drums)…five tons of glass falling over a cliff and landing on dynamite.” The act became more than an extension of Elvis’ gyrations, it became an extension of that to infinity, an orgy of noise so wound up that I felt that the dynamo that powered it would fail and fission into its primordial atomic state. Hendrix did not only pick the strings, he bashed them with the flat of his hand, he ripped at them, rubbed them against the mike, and pushed them with his groin into his amplifier. And when he knelt before the guitar as if it were a victim to be sacrificed, sprayed it with lighter fluid, and ignited it, it was exactly a sacrifice: the offering of the perfect, most beloved thing, so its destruction could ennoble him further.

But what do you play when your instrument is burnt? Where can you go next? “I don’t know, man,” said Hendrix with a laugh after the show. “I think this has gone about as far as it can go.” “In England they’ve reached a dead end in destruction,” said Brian Jones. “Groups like The Move and The Creation are destroying whole cars on stage.” Asked what it all meant, Andrew Loog Oldham, whose Rolling Stones have pushed far into their own violence kick, said, “If you enjoy it, it’s okay,” and the screaming, frightened but aroused audience apparently enjoyed it very much.

After a short and only mildly recuperative silence, on came The Mamas and the Papas, backed by vibes, drums, tympani, piano, and John Phillips’ guitar. They were great, everything The Mamas and the Papas should be. Mama Cass was in fine form, joking, laughing, and hamming it up like a camp Queen Victoria. Introducing “California Dreamin’,” she said, “We’re gonna do this song because we like it and because it is responsible for our great wealth.” When they finished, a wave of applause swept from the furthermost reaches of the crowd up to the stage and the hundred or more musicians, stagehands, and hangers-on dancing and shouting in the wings. “We’re gonna have this Festival every year,” said Mama Cass, “so you can stay if you want.” The roar of renewed applause almost convinced me that the crowd would patiently wait through the summer, fall, and winter, never stirring until next June.

* * *

Now that the Monterey Pop Festival is a day in the past, what did it prove about pop music? In a way, it proved little. Pop has few of the formal identifying qualities of jazz or folk, and so it did not prove that pop music is now here or there or anyplace. It did show that pop is still in a continuum with the blues, still loves and gets inspiration from the blues. It also showed that LSD and the psychedelics have tremendously broadened the minds of the young people making the new music.

It also demonstrated the continuing influence of The Beatles. Dozens of the other Monterey performers owe their being there to The Beatles. John Phillips was a folk singer until he heard The Beatles. “They were not so much a musical influence,” he said, “as an influence because they showed that intelligent people could work in rock and make their intelligence show.” Moreover, Monterey Pop ratified the shift away from folk music that has been going on for over two years. The Festival was, among other things, the largest collection of former folk singers and guitarists ever gathered in one place. Musicians trained in folk make up the bulk of the new rockers. This means that they came to rock ‘n’ roll, not as the only form, not the one they were trained in, but as an experiment, as a form they looked at first from the outside and rather distantly considered its possibilities.

That sense of experiment makes rock so lively today. The years of folk training, in which the two marks of status were knowledge of esoterica and the quality of performance, mean that the new rockers feel a need to push further and further ahead, and also that they are excellent players. The general level of musical competence was extremely high, and the heights hit by Mike Bloomfield and Jerry Garcia were as high as those reached by Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley, Doc Watson, and other immortal folk and rock guitarists.

In some ways it was surprising that there was little experimentation in some directions. No group went far afield from the basic instrumental lineup, staging, song lengths, and musical form. This indicates that rock is still rather traditional, that it is still a commercial art, that the public will not take leaps forward that are too wild, that the performers are still young and unsure of themselves, and that the rock revolution is still new.

This may all change, and if it does, the Festival will have played an important role. Brian Jones was right: for three days a community formed. Rock musicians, whatever their bag, came together, heard each other, praised each other, and saw that the scene was open enough for them to play as they liked and still get an audience. They will return to their own scenes refreshed and confident. The whole rock-hippie scene was vindicated. Even the police thought it was groovy. Monterey police chief Frank Marinello was so ecstatic that Saturday afternoon he sent half his force home. “I’m beginning to like these hippies,” he told reporters. “When I go up to that Haight-Ashbury, I’m going to see a lot of friends.” The fairgrounds, which at times held 40,000 people, far more than any other time in its history, were utterly peaceful. The tacit arrangement that there would be no busts for anything less than a blatant pot orgy was respected by both sides. When Mama Cass introduced “California Dreamin’” at 12:30 Monday morning, she said, “This whole weekend was a dream come true.”

Michael Lydon, a writer and musician, began reporting on pop music in the sixties. He is the author of the book Flashbacks. This piece originally appeared in the Criterion Collection’s 2002 edition of Monterey Pop.

via Monterey Pop: The First Rock Festival – From the Current – The Criterion Collection.

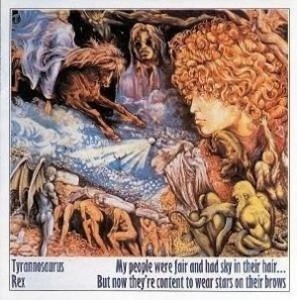

He famously scrapped the project in 1967, but some of its fundamental pieces would come out in drips and drabs on various Beach Boys releases: “Cabin Essence” thrown in the middle of the otherwise uneven 20/20, “Wind Chimes” in wispy, stripped-down form on the haphazardly compiled Smiley Smile. Even album centerpiece “Surf’s Up” got a whole record named after it. These small bits of insight would only further the mystery.

He famously scrapped the project in 1967, but some of its fundamental pieces would come out in drips and drabs on various Beach Boys releases: “Cabin Essence” thrown in the middle of the otherwise uneven 20/20, “Wind Chimes” in wispy, stripped-down form on the haphazardly compiled Smiley Smile. Even album centerpiece “Surf’s Up” got a whole record named after it. These small bits of insight would only further the mystery.